Where do we go next, with so much before us which we know not how to make sense of?

Both before and after the Vedic period depicted, there is to be found unfathomable swathes of twisting history, stretching beyond 5000 years.

What lay the destiny for Gujaratis? Through the Bronze Age, into the Harappan and Indus Valley Civilisations, the Mughal Empire. Through migration, through colonialism, then free of its chains into independence, but never freed of its impact. The most recent of my lineage, twice immigrants under colonial forces, resettled to Africa and thereafter displaced to the UK. Nothing but a passport and a room for 9 people. Awaiting racial violence and neglect, finding refuge in inbuilt familial values, unified with Afro-Caribbean migrants in common resistance.

Yet, but a light dusting onto the surface of an iceberg plunging miles deep into an abyss.

Our generation. Left with incomplete stories, missing pieces to the puzzle. Nods from our grandmothers, following stories of penury overcame.

Scars of their labour.

Sitting hands, silent gazes. Nobody but ourselves.

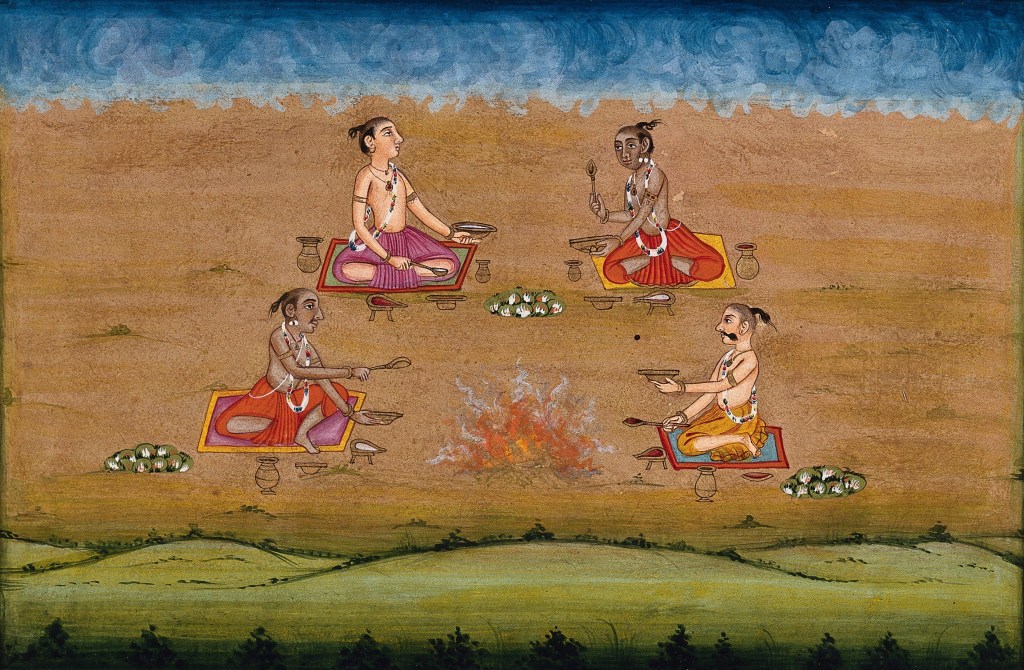

Maybe the priests in these depictions set it all out for us. A Vedic ritual for Agni, the divine personification of the fire of sacrifice, said to be the mouth of the gods, the carrier of the oblation, and the messenger between the human and the divine orders. Ruddy-hued and having two faces—one beneficent and one malignant. Depicted with three or seven tongues, hair that stands on end like flames, three legs, and seven arms. No solace, no basis. Metaphorically representing all transformative energy and knowledge.

Maybe our future is as our past, no more clear than it ever was. Transforming. The only common thread for us, found in our devotion and mercantile nature. The defining traits we learn from our elders.

Us, the immigrant population who always make it – wherever we are left to fend. And as Ludovico di Varthema said of Gujaratis in the 15th century; ‘…a certain race which eats nothing that has blood, never kills any living things… and these people are neither moors nor heathens… if they were baptized, they would all be saved by the virtue of their works, for they never do to others what they would not do unto them.’

The hallmark of our existence, and quite possibly the reason for our assimilation – tolerance, cohesion, high social capital, a non-hierarchical view of self and kin. The reason we have to change who we are to make it – just as our parents and grandparents did in the factories and markets of the Midlands.

The reason we feel disconcerted at work. On one hand trying hard to cling to our culture, and be courageous enough share it without hesitation – but on the other, having to walk a tight rope, forced to undertake a second life in order to be included and accepted.

And even the efforts of our second life – derived from a family history of striving to fit-in, often become a quirk for the amusement of others when they don’t quite pass the test. Made to feel abashed when answering the question of what we do on Christmas day.

The reaction to the rise of Rishi Sunak. His Diwali message, and the Downing Street Rangoli.

What is my culture? What duties do I have to it?

Who am I, and what seeds do I sow for those after me?